AKRX/Fresenius: Dispute Will Center on Materiality of Alleged FDA Data Integrity Issues

Mon 05/07/2018 15:04 PM

Event Driven Takeaways

The central dispute in Akorn’s lawsuit against Fresenius will be whether any FDA data integrity issues that Fresenius claims to have uncovered in its investigation of Akorn are significant enough to have a material adverse effect on Akorn’s business. Vice Chancellor Travis Laster, the presiding judge in the Delaware Chancery Court where the action is pending, has ordered trial for the week of July 9. This is a relatively tight turnaround time for what will likely be a fact-intensive dispute.

A material adverse effect is defined in the parties’ merger agreement in language that is fairly common for this type of contract. Delaware courts, for example in IBP, Inc. v. Tyson Foods (Del. Ch. 2001), have typically construed the term to mean “the occurrence of unknown events that substantially threaten the overall earnings potential of the target in a durationallity-significant manner.” This means that a “short-term hiccup” in a company’s earnings or performance would not be sufficient enough to constitute a material adverse effect.

Not surprisingly, the parties strongly disagree on the significance of the FDA data integrity shortcomings Fresenius claims to have identified. Akorn argues that any such issues are limited to drugs representing an insignificant aspect of Akorn’s business. Fresenius claims, after being tipped off by anonymous whistleblowers, to have unearthed a culture of non-compliance with FDA rules and fraudulent reporting by Akorn that was directed by Akorn’s executives. These issues, according to Fresenius, will “cripple” Akorn’s operations until they can be sufficiently rectified.

A key point in the dispute will center on the concrete evidence that Fresenius relies on to establish that Akorn’s business is materially affected by the data integrity issues. Akorn’s counsel, at last week’s status hearing, made a compelling point that Fresenius should not need extensive discovery since it claims to have sufficient evidence, at present, of a material adverse effect. Claiming to need significant additional documentation could risk Fresenius’ credibility. Akorn argued to the court that Fresenius is not entitled to file a lawsuit and then see if a material adverse effect develops thereafter. Rather, it must justify its decision to terminate the merger agreement at the time it chose to abandon the transaction.

Below is a preliminary overview of the manner in which the companies’ dispute could develop leading up to and through the July 9 trial.

Pertinent Contractual Provisions

A close reading of the merger agreement indicates that Fresenius may unilaterally terminate the agreement under Section 7.01(c) if Akorn breaches certain of its representations and warranties under Section 6.02(a) and Section 6.02(b). Specifically, Section 6.02(a) lists out various representations and warranties under two categories. The first category, Section 6.02(a)(i), contains a specific list of reps and warranties that, if breached, would give Fresenius an easy out. Fresenius is not limited in any way to prove “materiality” or an MAE with respect to the breach of representations and warranties listed in this category. However, Section 6.02(a)(i) does not explicitly mention Section 3.18, which requires Akorn to be in compliance with FDA rules and regulations, including data integrity issues.

Section 3.18 ties into the termination clause through Section 6.02(a)(ii), the second category of breaches that would allow Fresenius to terminate the merger. However, the language contained in Section 6.02(a)(ii) requires Fresenius to also prove “materiality” with respect to any breach. In other words, if Fresenius relies on Section 3.18 and Akorn’s alleged FDA data breaches, then it must also prove that such breaches satisfy Delaware’s onerous “materiality” standards.

The existence of Section 3.18 in the merger agreement arguably indicates that before they agreed to merge, both Akorn and Fresenius were aware of FDA-related issues and the risk of non-compliance that generally troubles the pharmaceutical industry.

Fresenius also claims Akorn violated two covenants in the merger agreement: (1) Section 5.01, which requires Akorn to operate its business in the “ordinary course;” and (2) Section 5.05, which obligates Akorn to provide “reasonable access” to records and company officials.

Delaware Case Law

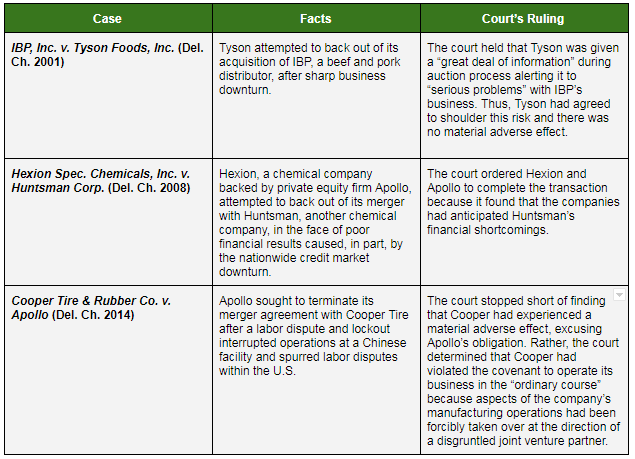

The table below contains three prominent Delaware cases that address a buyer’s claims that it is entitled to terminate a merger agreement due to the seller experiencing a material adverse effect. These cases are frequently cited by antitrust practitioners and will undoubtedly be addressed in some manner by the parties in Akorn’s lawsuit against Fresenius.

Akorn will likely argue that this case is comparable to Tyson Foods and Hexion because the parties engaged in what Akorn has described as an extensive due diligence process leading up to the merger. In those two cases, the court found that the buyers had effectively assumed the risk of poor financial performance by the sellers based on information made available prior to signing the merger agreement and thus were not permitted to back out of the transaction. According to Akorn, Fresenius was not concerned about FDA data integrity issues during the due diligence process and did not request information related to these issues. Rather, Akorn claims that Fresenius only became concerned about FDA data integrity issues when it determined it could use that issue as a pretext to back out of the deal over which Fresenius developed buyer’s remorse.

Fresenius, in response, will probably claim that these two cases are inapplicable because it did not know about the FDA data integrity issues before entering into the merger agreement. To support this position and differentiate these cases, Fresenius will likely point to Section 3.18 of the merger agreement, where Akorn explicitly stated that it was in full compliance with FDA rules, and had been since July 2013. For this reason, Fresenius could therefore argue that it was aware of the possibility of FDA data integrity issues and the parties explicitly agreed that Akorn would shoulder this risk.

Fresenius could also point to the Cooper Tire case in which the Delaware court found that a labor strike and other obstructive efforts at a Chinese manufacturing plant amounted to a violation of the merger agreement covenant to operate the business in the “ordinary course.” The court in that case sidestepped the issue of whether a material adverse effect had occurred, determining that it need not decide that issue due to its finding that the “ordinary course” covenant had not been met. In its counterclaim to Akorn’s complaint, Fresenius raises a similar argument - that Akorn’s fraud and misreporting to the FDA constitutes a failure to operate the company in the “ordinary course.”

Akorn will likely argue that Fresenius cannot point to any issues that rise to the level of those experienced by Cooper Tire. In addition, Akorn will likely argue that the companies explicitly tied FDA compliance to a material adverse effect requirement in the agreement. As a result, Akorn could claim that Fresenius cannot circumvent that requirement by shoehorning complaints about FDA deficiencies into a separate provision that does not contain a materiality requirement.

How Material are Akorn’s Alleged Data Integrity Failures?

Turning to the issue of the materiality of Akorn’s alleged data integrity shortcomings, Fresenius claims that an Akorn executive knowingly directed the submission of fraudulent testing data to the FDA in connection with an application to market azithromycin. This scheme, according to Fresenius, has “infected” at least five other Akorn products.

Akorn claims that azithromycin and five other drug products in question either have never been marketed or are not currently being marketed and were never forecasted to form a material portion of Akorn’s future earnings. This would mean that any issues Fresenius has unearthed relating to the drugs will not amount to a material adverse effect on Akorn’s business.

According to Akorn’s SEC filings, the company submitted five new Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA, filings in 2017. In the prior year ending Dec. 31, 2016, the company submitted 12 ANDA filings while in 2015, it submitted 18 ANDA filings and one New Drug Application, or NDA, filing to the FDA. As of Dec. 31, 2017, Akorn had 68 ANDA filings under FDA review.

If the data integrity issues Fresenius has discovered are in fact limited, as Akorn claims, to azithromycin and five other drugs, it is possible that those FDA data integrity failures would not materially alter the company’s growth prospects associated with its vast pipeline of new drugs.

On its 2017 earnings call, Akorn’s CEO Raj Rai confirmed that while the company’s pipeline portfolio contains a mix of high- and low-value products, on average, the company expects to bring in roughly $3 million to $5 million in net revenues per product. During the call, Rai also mentioned that revenues associated with new products were “weighted towards the back half of the year” and that there was likely to be a “healthy carryover effect” with higher revenues in 2018 versus the second-half contribution in 2017.

It is, therefore, fair to assume that Akorn’s new products, on average, can be expected to generate roughly $6 million to $10 million in annualized net revenues per product. If, as Akorn claims, the alleged data integrity issues are restricted to azithromycin and five other drugs, that would call into question approximately $60 million in annual net revenues at the upper end. In juxtaposition to Akorn’s overall 2017 annual net revenues of $841 million, the impact of the these alleged data integrity failures would amount to roughly 7% of Akorn’s annual net revenues.

While no Delaware court has ever decided to allow a buyer to walk away from a deal based on a finding of a material adverse effect, it remains to be seen whether a revenue impact figure of about 7% would be in the ballpark of the relatively onerous “materiality” standard that Fresenius must meet.

Akorn’s counsel reiterated the company’s position during the hearing last week that azithromycin and the five other drugs “had no revenues associated with it.” However, it is not clear if Fresenius has evidence to prove that Akorn’s FDA violations are more systemic in nature, with wide-ranging ramifications for the company’s entire portfolio of pipeline drugs. If it is found that the latter is true, then the math would work against Akorn, making it easier for Fresenius to cross the “materiality” barrier.

Event Driven’s coverage of this transaction can be found HERE.

--Shrey Verma and Matt McLellan

- The dispute between Akorn and Fresenius over whether the Delaware Chancery should order the parties to complete the merger will focus on how significant any FDA data integrity issues are to Akorn’s overall business.

- Specifically, the parties disagree over the extent of the FDA data integrity issues and whether any such issues will have a materially adverse effect on Akorn’s business as a whole.

- Based on Akorn’s 2017 earnings call, while the company’s pipeline portfolio contains a mix of high- and low-value products, on average, the company expects to bring in roughly $6M to $10M in annualized net revenues per product. It remains to be seen whether the revenue impact from azithromycin and five other drugs would be in the ballpark of the relatively onerous “materiality” standard that Fresenius must meet.

- Fresenius also argues that Akorn’s conduct violates certain covenants in the merger agreement. This could be a mostly fallback argument from Fresenius based on recently decided Delaware Chancery Court cases.

- Delaware courts have not directly permitted a party to walk away from a merger based on a claimed material adverse effect. However, the case law is fact-specific and may give Fresenius an avenue to succeed on this claim.

The central dispute in Akorn’s lawsuit against Fresenius will be whether any FDA data integrity issues that Fresenius claims to have uncovered in its investigation of Akorn are significant enough to have a material adverse effect on Akorn’s business. Vice Chancellor Travis Laster, the presiding judge in the Delaware Chancery Court where the action is pending, has ordered trial for the week of July 9. This is a relatively tight turnaround time for what will likely be a fact-intensive dispute.

A material adverse effect is defined in the parties’ merger agreement in language that is fairly common for this type of contract. Delaware courts, for example in IBP, Inc. v. Tyson Foods (Del. Ch. 2001), have typically construed the term to mean “the occurrence of unknown events that substantially threaten the overall earnings potential of the target in a durationallity-significant manner.” This means that a “short-term hiccup” in a company’s earnings or performance would not be sufficient enough to constitute a material adverse effect.

Not surprisingly, the parties strongly disagree on the significance of the FDA data integrity shortcomings Fresenius claims to have identified. Akorn argues that any such issues are limited to drugs representing an insignificant aspect of Akorn’s business. Fresenius claims, after being tipped off by anonymous whistleblowers, to have unearthed a culture of non-compliance with FDA rules and fraudulent reporting by Akorn that was directed by Akorn’s executives. These issues, according to Fresenius, will “cripple” Akorn’s operations until they can be sufficiently rectified.

A key point in the dispute will center on the concrete evidence that Fresenius relies on to establish that Akorn’s business is materially affected by the data integrity issues. Akorn’s counsel, at last week’s status hearing, made a compelling point that Fresenius should not need extensive discovery since it claims to have sufficient evidence, at present, of a material adverse effect. Claiming to need significant additional documentation could risk Fresenius’ credibility. Akorn argued to the court that Fresenius is not entitled to file a lawsuit and then see if a material adverse effect develops thereafter. Rather, it must justify its decision to terminate the merger agreement at the time it chose to abandon the transaction.

Below is a preliminary overview of the manner in which the companies’ dispute could develop leading up to and through the July 9 trial.

Pertinent Contractual Provisions

Representations and Warranties

A close reading of the merger agreement indicates that Fresenius may unilaterally terminate the agreement under Section 7.01(c) if Akorn breaches certain of its representations and warranties under Section 6.02(a) and Section 6.02(b). Specifically, Section 6.02(a) lists out various representations and warranties under two categories. The first category, Section 6.02(a)(i), contains a specific list of reps and warranties that, if breached, would give Fresenius an easy out. Fresenius is not limited in any way to prove “materiality” or an MAE with respect to the breach of representations and warranties listed in this category. However, Section 6.02(a)(i) does not explicitly mention Section 3.18, which requires Akorn to be in compliance with FDA rules and regulations, including data integrity issues.

Section 3.18 ties into the termination clause through Section 6.02(a)(ii), the second category of breaches that would allow Fresenius to terminate the merger. However, the language contained in Section 6.02(a)(ii) requires Fresenius to also prove “materiality” with respect to any breach. In other words, if Fresenius relies on Section 3.18 and Akorn’s alleged FDA data breaches, then it must also prove that such breaches satisfy Delaware’s onerous “materiality” standards.

The existence of Section 3.18 in the merger agreement arguably indicates that before they agreed to merge, both Akorn and Fresenius were aware of FDA-related issues and the risk of non-compliance that generally troubles the pharmaceutical industry.

Covenants

Fresenius also claims Akorn violated two covenants in the merger agreement: (1) Section 5.01, which requires Akorn to operate its business in the “ordinary course;” and (2) Section 5.05, which obligates Akorn to provide “reasonable access” to records and company officials.

Delaware Case Law

The table below contains three prominent Delaware cases that address a buyer’s claims that it is entitled to terminate a merger agreement due to the seller experiencing a material adverse effect. These cases are frequently cited by antitrust practitioners and will undoubtedly be addressed in some manner by the parties in Akorn’s lawsuit against Fresenius.

Akorn will likely argue that this case is comparable to Tyson Foods and Hexion because the parties engaged in what Akorn has described as an extensive due diligence process leading up to the merger. In those two cases, the court found that the buyers had effectively assumed the risk of poor financial performance by the sellers based on information made available prior to signing the merger agreement and thus were not permitted to back out of the transaction. According to Akorn, Fresenius was not concerned about FDA data integrity issues during the due diligence process and did not request information related to these issues. Rather, Akorn claims that Fresenius only became concerned about FDA data integrity issues when it determined it could use that issue as a pretext to back out of the deal over which Fresenius developed buyer’s remorse.

Fresenius, in response, will probably claim that these two cases are inapplicable because it did not know about the FDA data integrity issues before entering into the merger agreement. To support this position and differentiate these cases, Fresenius will likely point to Section 3.18 of the merger agreement, where Akorn explicitly stated that it was in full compliance with FDA rules, and had been since July 2013. For this reason, Fresenius could therefore argue that it was aware of the possibility of FDA data integrity issues and the parties explicitly agreed that Akorn would shoulder this risk.

Fresenius could also point to the Cooper Tire case in which the Delaware court found that a labor strike and other obstructive efforts at a Chinese manufacturing plant amounted to a violation of the merger agreement covenant to operate the business in the “ordinary course.” The court in that case sidestepped the issue of whether a material adverse effect had occurred, determining that it need not decide that issue due to its finding that the “ordinary course” covenant had not been met. In its counterclaim to Akorn’s complaint, Fresenius raises a similar argument - that Akorn’s fraud and misreporting to the FDA constitutes a failure to operate the company in the “ordinary course.”

Akorn will likely argue that Fresenius cannot point to any issues that rise to the level of those experienced by Cooper Tire. In addition, Akorn will likely argue that the companies explicitly tied FDA compliance to a material adverse effect requirement in the agreement. As a result, Akorn could claim that Fresenius cannot circumvent that requirement by shoehorning complaints about FDA deficiencies into a separate provision that does not contain a materiality requirement.

How Material are Akorn’s Alleged Data Integrity Failures?

Turning to the issue of the materiality of Akorn’s alleged data integrity shortcomings, Fresenius claims that an Akorn executive knowingly directed the submission of fraudulent testing data to the FDA in connection with an application to market azithromycin. This scheme, according to Fresenius, has “infected” at least five other Akorn products.

Akorn claims that azithromycin and five other drug products in question either have never been marketed or are not currently being marketed and were never forecasted to form a material portion of Akorn’s future earnings. This would mean that any issues Fresenius has unearthed relating to the drugs will not amount to a material adverse effect on Akorn’s business.

According to Akorn’s SEC filings, the company submitted five new Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA, filings in 2017. In the prior year ending Dec. 31, 2016, the company submitted 12 ANDA filings while in 2015, it submitted 18 ANDA filings and one New Drug Application, or NDA, filing to the FDA. As of Dec. 31, 2017, Akorn had 68 ANDA filings under FDA review.

If the data integrity issues Fresenius has discovered are in fact limited, as Akorn claims, to azithromycin and five other drugs, it is possible that those FDA data integrity failures would not materially alter the company’s growth prospects associated with its vast pipeline of new drugs.

On its 2017 earnings call, Akorn’s CEO Raj Rai confirmed that while the company’s pipeline portfolio contains a mix of high- and low-value products, on average, the company expects to bring in roughly $3 million to $5 million in net revenues per product. During the call, Rai also mentioned that revenues associated with new products were “weighted towards the back half of the year” and that there was likely to be a “healthy carryover effect” with higher revenues in 2018 versus the second-half contribution in 2017.

It is, therefore, fair to assume that Akorn’s new products, on average, can be expected to generate roughly $6 million to $10 million in annualized net revenues per product. If, as Akorn claims, the alleged data integrity issues are restricted to azithromycin and five other drugs, that would call into question approximately $60 million in annual net revenues at the upper end. In juxtaposition to Akorn’s overall 2017 annual net revenues of $841 million, the impact of the these alleged data integrity failures would amount to roughly 7% of Akorn’s annual net revenues.

While no Delaware court has ever decided to allow a buyer to walk away from a deal based on a finding of a material adverse effect, it remains to be seen whether a revenue impact figure of about 7% would be in the ballpark of the relatively onerous “materiality” standard that Fresenius must meet.

Akorn’s counsel reiterated the company’s position during the hearing last week that azithromycin and the five other drugs “had no revenues associated with it.” However, it is not clear if Fresenius has evidence to prove that Akorn’s FDA violations are more systemic in nature, with wide-ranging ramifications for the company’s entire portfolio of pipeline drugs. If it is found that the latter is true, then the math would work against Akorn, making it easier for Fresenius to cross the “materiality” barrier.

Event Driven’s coverage of this transaction can be found HERE.

--Shrey Verma and Matt McLellan

This article is an example of the content you may receive if you subscribe to a product of Reorg Research, Inc. or one of its affiliates (collectively, “Reorg”). The information contained herein should not be construed as legal, investment, accounting or other professional services advice on any subject. Reorg, its affiliates, officers, directors, partners and employees expressly disclaim all liability in respect to actions taken or not taken based on any or all the contents of this publication. Copyright © 2024 Reorg Research, Inc. All rights reserved.